Harvesting Honey–A Labor of Love

Sitting in the middle of my kitchen is a three-story hive box with thirty frames of honey that needs to be extracted, filtered, and poured into jars.

My apiary is small–just two hives. Taking the honey is quite a labor-intensive activity. But it brings its own kind of joy. As pollinator populations decrease, keeping bees is a small thing I can do for all of us . . . for our planet.

This electric honey extractor holds four frames; honey is spun out through centrifugal force and drains through the spigot

The stainless steel honey extractor, washed and scrubbed, has been pushed over by the oven to make a little space in my already-small kitchen.

Today, I washed the countertops, my stove, and even the sink with hot soapy water and bleach. Then after a thorough wipe-down, I stretched sheets of aluminum foil over the countertop. The extraction process started with four frames.

It’s a simple process. I set the four frames of honey on the foil-covered counter. Using a hot knife, I open the capped cells on both sides of the frames and put them in the honey extractor. Beneath the machine’s spigot, I’ve already positioned a five-gallon bucket with strainer attached. I start the machine on a slow speed and open the spigot.

Each of the five gallon and two-gallon buckets were previously washed and covered with strainers. These are held in place with heavy duty duct tape wrapped around the mouths. Switching out a full bucket for an empty one is easy when the buckets are prepped for use before the extraction starts.

Springtime honey appears golden in the frames whereas autumn honey is often darker (depending on what’s flowering, but often star thistle and eucalyptus, in my area)

I expect a yield of about thirty-five gallons this time. I lost one hive . . . more on that later, but, in all, it looks to be a good honey harvest for our family and friends.

As soon as I extract all the honey, I’ll start bottling it and affixing labels. It’s a process that will take several days to complete.

Tasting, smelling, and seeing all this golden, delicious honey that the bees created warms my heart. When we take care of them, they take care of us. And we always leave plenty of honey in the hives for the bees to eat throughout the winter.

* * *

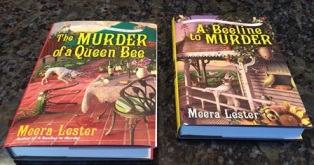

If you enjoy reading about farmette topics (including gardening, beekeeping, and delicious recipes), check out my Henny Penny Farmette cozy mysteries series from Kensington Publishing.

These novels are chocked full of recipes, farming tips, and sayings as well as a charming cozy mystery.

See, http://tinyurl.com/hxy3s8q

This debut novel launched the Henny Penny Farmette series of mysteries and sold out its first press run. It’s now available in mass market paperback and other formats.

See, http://tinyurl.com/h4kou4g

JUST RELEASED! This, the second cozy mystery in the Henny Penny Farmette series, is garnering great reviews from readers and industry publications.

My books are available through online retailers such as Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo Books, and Walmart as well as from traditional bookstores everywhere.

Spinning Liquid Gold

Honey is the liquid gold that we harvest from our backyard honeybee hives. Until recently, I had to take frames out of the hives, open the cap cells, and drain the honey through a strainer into a bucket.

Just before Mother’s Day, my hubby purchased an electric honey extractor. He set it up in the kitchen. This weekend, we plan to open the hives and harvest some frames, giving our new machine a test run.

A hand-cranked or electric honey extractor makes it much easier to get honey out of the wooden frames. After the capped cells are opened with a hot knife, the frame goes into the machine. It spins honey against the cylinder walls and the sweet liquid then drains out the spigot.

I use a fabric paint strainer taped over a five-gallon honey bucket (also with a spigot) to filter the honey and fill the jars. The jar of liquid gold is then labeled and ready to distribute to customers and friends.

* * *

If you like reading about keeping bees and chickens, harvesting honey, and creating delicious recipes, check out my novels in the Henny Penny Farmette series. Besides offering an intriguing cozy mystery, these books are chocked full of farm sayings, tips for gardening, yummy recipes, and much more.

My novels are published by Kensington Publishing and are available through online stores of Barnes & Noble, Amazon.com, Walmart, Kobo and conventional bookstores everywhere.

A BEELINE TO MURDER is the debut novel and THE MURDER OF A QUEEN BEE is the second book in the Henny Penny Farmette series from Kensington Publishing.

Pulling Honey–A Bee-eautiful Sight to See

Nothing compares to the reward of pulling honey from a hive when you are a beekeeper. Over the last two days, this is what I’ve done with the help of my world-class beekeeper neighbor who knows more about keeping honeybees than anyone I’ve ever met.

Pictured is a Henny Penny Farmette honey bucket with strainer taped on and bits of wax in the honey on top

His wife helped me scrape off the bee glue from each frame and then open the capped cells (a must) before draining the honey. We then used their machine that can spin twenty frames at a time. It has an electric motor and a control to increase or decrease the speed. Use slow speed to begin and then when the frames grow lighter, you increase the speed.

In all, I spun four hive boxes full (ten frames each), except for one box that had fewer because we left two frames behind in the apiary. They still had babies in them.

We taped fine-mesh filters over the tops of several five-gallon buckets. To spin the honey out of the first eighteen frames took many hours, from noon to about ten o’clock at night. We left the machine spigot open all night to allow the draining to continue into the bucket. The filters caught bits of wax and even the occasional dead bee, ensuring the honey would be perfectly clean and ready to bottle.

I drained honey from the ten frames in each of my hive boxes–two of my hive boxes held the large frames and two held smaller frames. In all, we spun and drained enough honey to fill three five-gallon buckets and about one-fourth of a two and one-half gallon bucket.

Not a bad yield for a fairly young hive and during summer in a drought year when pollen-laden flowers are not be as plentiful. It’s a bee-eautiful sight to see!

Uncapping, Draining, and Straining a Frame of Honey

I have frames of honey wrapped in foil in my kitchen freezer. These frames haven’t yet been uncapped, drained, and strained for bottling.

Since the weather on the farmette has turned springlike, I can’t put this chore off any longer. Those frames have to come out of the freezer. They’re from late October. I’d wrapped them in aluminum foil and froze them until I could find time to work with them.

Once a frame had defrosted, I needed to open the cells of wax, capped by the bees. Opening capped cells becomes easier if you use a hot knife. I run mine through a gas burner and wipe frequently. After the cells are opened on both sides of the frame, I stand the rectangular wooden frame in a freshly washed two- or five-gallon bucket and cover the bucket with plastic wrap until the honey drains out.

Then, of course, the honey collected needs to be filtered. I use a bucket over which I’ve secured a thin painter’s net for straining paint. As the honey drains through, I twist around a large wooden spoon to tighten. Eventually, all that is left in the net strainer are pieces of wax. Many backyard beekeepers run honey through the straining process twice before bottling.

Using a coat hanger, I hang the frames (from which I harvested the honey) in a tree near the apiary. The bees will do the work of removing all traces of honey, leaving only wax. At this point, I’ll freeze the frames before reusing them.

This is a very old fashion way of harvesting honey. There are modern appliances and other tools, including an electric hot knife and honey extractor machines, that serious beekeepers can use. But the old ways, although more laborious, still work.

Facebook

Facebook Goodreads

Goodreads LinkedIn

LinkedIn Meera Lester

Meera Lester Twitter

Twitter