Archive for the 'Pests' Category

Worst Apricot Aphids Ever

The farmette apricot trees have been shedding leaves as winter approaches. I’ve recently noticed ants in the tree and leaves that are sticky. Further investigation revealed that the tree leaves are covered with apricot aphids seeking moisture and nutrients from the leaves.

The local garden center’s expert explained that those tiny aphids know when the seasons are changing. As leaves fall, they take in nutrients to tide them over to spring. Ants often signal a pest problem with the tree long before you notice the presence of aphids.

Like many pests attacking apricot trees, aphids overwinter as eggs (smaller than a grain of rice). These eggs are hidden in the cracks and crevices of the bark, branches, and twigs.

During this past fall (2021), aphids flew around our apricot and other fruit trees like ash on a windy day. They consumed leaf and stem sap that resulted in a sticky substance known as honeydew, a sticky waste product left on the leaves.

It’s worth mentioning that aphids aren’t the only apricot tree pests. A partial list of other apricot tree pests includes:

1. mealybugs

2. earwigs

3. mites

4. leaf roller

5. apricot-peach twig borer

6. scale

7. spider mites

Although we don’t like using any kind of spray out of concern over toxicity to our honeybees, our local garden center recommends using an organic spray such as Captain Jack’s (approved for organic farming). This time of year, it’s a good idea to apply the spray after pruning the trees.

Doing a good job with pruning and spraying means that the aphids might not be such a problem come spring.

____________________________________________________________________________

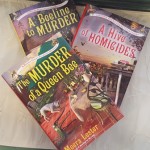

Enjoy reading about farm topics? Check out my Henny Penny Farmette series of cozy mysteries. Chocked full of farm trivia and helpful advice for keeping chickens and bees and growing heirloom fruit and vegetables, all three novels are available online and in bookstores everywhere.

A Beeline to Murder–When the town’s celebrity pastry chef is found dead, Abby Mackenzie (a former cop who supplies the chef with her organic lavender honey) discovers the chef’s secret private life suggests the killer might be local.

The Murder of a Queen Bee–The botanical shop owner and friend of Abby Mackenzie doesn’t make it to a party where she’s the guest of honor. Her death leads Abby to speculate that friends of the deceased might be hiding her killer.

A Hive of Homicides–Abby attends a vow-renewal party of her best friend and is an ear witness to the murder of the newly arrived re-married couple. The husband’s philandering past establishes a pool of suspects but Abby is convinced that there’s more to the murder a scorned lover’s revenge.

What’s Eating the Chicken Eggs?

Several times over the last month or so, I’ve traipsed to the hen house to collect eggs and found a broken egg or one with a hole in the shell and the egg otherwise intact.

I wondered if one of the chickens had gone rogue and was pecking the egg that either she or one of the other hens had laid.

My flock is small and they usually lay their eggs during the morning hours, using the afternoon to free range and forage.

Each time I heard a cackle, I sprinted to the chicken house to see who was raising the ruckus and whether or not she’d pecked her egg.

Finally, I caught one of my Silver-Lace Wyandotte hens on the nest. With her head twisted behind and under her wing, I could not tell what was going on. I slipped my hand under her, causing her head to jerk around. It appeared I had caught her in the act as her beak was covered with yolk.

So I thought I’d solved the mystery. My solution was to remove each egg as soon as the hen laid it. If I removed the eggs, any temptation for the chickens to peck the eggs would be eliminated, too. But running for every chicken squawk became so time consuming, I finally stopped.

To my utter surprise, there were no more broken eggs. That didn’t make sense. However, during the whole ordeal with the broken eggs, I’d been smelling a skunk. When my closest neighbor said a skunk had been raiding his coop for the eggs, I began to think I had wrongly accused my poor Wyandotte.

Indeed, since my neighbor took care of the skunk (by trap, I believe), my hens are producing eggs every day and none have holes or are cracked. I’m now thinking the skunk was the egg robber.

That experience got me thinking about other predators that will eat chicken eggs (and chickens, too). The list includes opossums, weasels, rats, snakes, minks, foxes, wild dogs, coyotes, raccoons, hawks, and owls. So, even if I’ve got a nice hen house and a run with a wire roof, it seems that a predator motivated by a good meal with find a way in.

Fire Blight Can Ravage a Pear Tree or Take Down an Orchard

I’ve discovered limb tips, fruit, and blossoms blackened by fire blight in my Bartlett pear tree. That means dealing with the disease quickly or losing tree.

While there are dozens of other types of fruit trees on the farmette, there are no other pear trees. Sadly, this one is in bad shape because of a widespread infection by the bacteria Erwinia amylovora.

The blight started last summer and, despite spraying to control it, the disease has overwintered in the bark of the tree to reappear with the emergence of blossoms this year. Disease spread is helped along by the bees.

Fire blight’s vicious cycle and must be broken if the tree is to survive. The life cycle of blight can be seen at a glance at http://nysipm.cornell.edu/factsheets/treefruit/diseases/fb/fb_cycle.gif

Treatment starts with a vigorous pruning of the affected limbs. That means cutting back twelve inches from the site of the blackened area of fire blight. The disease is highly contagious, so the cuttings must not be recycled or composted. Burning them is recommended.

Also, minimizing the amount of tree blight inoculum in the orchard is important as this disease can also spread to other pear trees, apples, quince, raspberries, and fire-thorn bushes. Cornell recommends a regular spraying program using an appropriate bacteriocide to save fruit trees infected with fire blight.

The saddest thing of all for me is that the tree was once beautiful and healthy and (even now) is loaded with fruit. I hate to think of not being able to save this lovely pear tree. Since most pear cultivars are susceptible to fire blight, it might make sense for me to plant a Seckel Pear tree since it is less susceptible to this highly contagious disease that can destroy a single tree or ravage the entire orchard.

Blooms over the Garden Gate

The nectarine trees are susceptible to Peach Leaf Curl and usually, I try to spray them three times before the next year’s blooms. Alas, this year, I didn’t complete the task before the tree broke bud.

Elsewhere, the almonds, apricots, and apples are blooming. So are some of the roses–Lady Banks, for example. Also, Fiesta and the beautiful Iceberg rose in the front of our house.

My neighbor’s two almond trees are covered in blooms of white blossoms. Last Friday, when I contacted a local beekeeper business, I was told they were closed to move their hives of bees out to pollinate the almond orchards. Farmers pay the beekeepers for “renting” those hives of industrious little bees for the job of pollinating their crops.

This is supposedly “bare root” season, but the warm weather coupled with the rain we had in December seems to have brought us an early spring. If you look over my garden gate, you will see signs of it everywhere.

Spate of Warm Weather Brings Out Early Blosssoms

While schools across the nation are taking snow days because of frigid temperatures, the fruit trees on my Bay Area farmette are showing signs of bud swelling and early blossoming because of a winter heat wave.

Cities around the San Francisco Bay are experiencing early January temperatures of 70-plus degrees Fahrenheit, breaking weather records in some areas. Mother Nature certainly behaves strangely at times.

My five-variety apple tree and the early Desert Gold peach trees are covered with buds that are already showing color. I haven’t as yet gotten around to the winter pruning and spraying with organic oil. Maybe if there’s no wind today, I’ll squeeze that chore in with the others.

I did cut back the Washington navel orange that is infected with Leaf Miner, a pest that’s crossed the United States from Florida. It attacks new leaves, so I’m thinking if I prune and spray now before spring is in full swing, maybe I won’t lose this tree. Curiously, the pest hasn’t widely infected my blood orange trees but there are signs of it in the leaves of our Satsuma seedless tangerines.

Elsewhere, I’ve done deep digging in the chicken run and added some wood chips and leaf material for compost.

The tea roses have been pruned back to 12 to 18 inches and old canes removed. I’m torn between wanting to add more roses in the beds in front of the bamboo plants on the east/west axis of our property or adding more lavender and sunflowers, favored by the bees.

Tomorrow, I’ll open and inspect my bee hives. I left honey stores this past autumn instead of harvesting. But if the bees have gone through all the honey, then I’ll have to add bee food until we get the first early bulb blooms and wildflowers. The French perfume lavender that the bees love is about the only bloom (bee food) in the garden now. Luckily, I planted a lot of it.

The farm chores don’t just seem endless, they are. But whether the work is daily, weekly, or seasonal, there’s something deeply rewarding–even magical–about living close to the earth in harmony with cycles of seasons and the rhythms of nature. But I admit, it is a little strange to have such warm weather when winter has only just started.

Leafminer Larvae Can Destroy Young Citrus Trees

The new leaves on nearly all our citrus trees show signs of the presence of the citrus leafminer. The local garden center representative explained this pest is ravaging trees in our area. The pest’s name is fitting–its larvae tunnel into new leaves creating mining tunnels.

This pest came to California in 2000 by way of Florida, where it showed up in 1993 and began steadily moving westward. The citrus leafminer is native to Asia, but in the 1940s, it showed up in Australia. From there, it began to appear in other citrus-growing regions of the world.

The citrus leafminer is a small, light-colored moth. Its forewings are irridescent. The wing tips have a black spot. The hind wings and its body are white. Look for a serpentine tunnel on a new leaf and inside the tunnel is thin dark line, the frass (or feces) trail.

The citrus leafminer burrows into new leaves, creating tunnels that, in turn, make for an exotic mosaic appearance on the leaves

In its last stage before adulthood, the larva causes the leaf the curl up. The curling is the result of the larva rolling the leaf end around itself in order to pupate as it becomes an adult moth.

Older, hardened citrus leaves are not at risk. The citrus leafminer attacks only young, shiny, green, new leaves. Young trees are perhaps at greatest risk.

Citrus growers should prune their trees only once each year because pruning causes a flush of new growth, open for attack. Because of the difficulty of getting the product inside the tunnels, chemical control is not recommended. Also, traps using a pheromone attracts only the male moth. It gets stuck inside, but this won’t eliminate the citrus leafminer population.

Biological control is accomplished through parasites and predators. The non-stinging wasps, Cirrospilus and Pnigalio species are particularly effective against citrus leafminer since the parasites lay eggs inside the leafminer tunnels, either inside or on the top of the citrus leafminer larvae. The parasite egg hatches and the parasite larvae eat the leafminer larva. You don’t have to put these pests in your garden. They are attracted to citrus just like the leafminer is.

Nature has a powerful checks-and-balance ecosystem that works best when growers do not spray insecticides. Pesticides and insecticides disrupt predator activity and nature’s inherent balance.

To-Do List of Chores for the Fall Garden

From my office widow, I look out over what once was a lush and thriving garden. Not so today.

I can hardly bear to gaze upon the sorrowful, dried tomato vines that for me have come to symbolize the severity of the extreme drought on California gardens.

Now that fall will soon arrive, I’ll toss onto the compost pile those vines along with others from pumpkins and hard-shelled squash.

So with the garden cleared, I’m thinking ahead to next year, ever hopeful we’ll get rain rather than a repeat of dry conditions like this past year.

To ensure the viability of our fruit trees, citrus trees, and various berries through the fall and winter, there is a spray regimen to be initiated. I’ll add it to my long list of chores that will need to be done.

MY FALL CHECKLIST FOR THE GARDEN

Turn the soil, add amendments like compost to hold in the water.

Prepare new beds.

Build cold frames and 4- x 6- foot boxes for new raised beds.

Cut the canes of blackberries (berries only set up on two-year-old canes that won’t again produce; cut to ensure new fruiting canes will take their place).

Prune away the spent floricanes of red raspberries, once they’ve produced fruit.

Clean up around the bases of all trees and evergreen plants; add mulch.

Also remove all leaves at the base of all fruit trees and dispose.

Remove rose leaves after blooming season, cut canes to 18 inches, and spray for diseases and pests.

Stake young trees so they’ll survive windy winters, growing straight and tall.

Treat the trees with an organic spray (one containing copper and protector oil) to prevent fungal disease and pests.

Get out the frost cloth in readiness to cover tender citrus trees.

Prune back the hydrangeas.

Plant fall bulbs for spring flowering.

Drought Hurts Honeybees, Too

The star thistle blooms in yellow bursts of color over the brown, drought-parched hills of the Bay Area during summer. Widely considered a noxious, invasive weed, the yellow star thistle’s blooms serve as a source of food for the honeybees during drought conditions when flower sources become scant.

While naturalists, government officials, land management people, ranchers, gardeners, farmers, and road and park maintenance workers consider the yellow star thistle challenging to control, others lament indigenous plants suffer or die because the yellow star thistle depletes the soil of moisture. Its one redeeming value appears to be as a food source for the bees.

Local beekeepers understand the value of the yellow star thistle during severe drought when water rationing in many counties mean few if any flowers are left blooming in August and September. While the plant’s nectar is great for the bees, it’s bad news for horses. Feeding on yellow star thistle over time can cause a horse malady known as chewing disease.

Also called St. Barnaby’s thistle and yellow cockspur, the yellow star thistle’s long tap root keeps it going while other plants around it die from lack of water. In Europe where the plant is indigenous, it is held in check by other plants that have co-evolved with it and by herbivores, the enemies of yellow star thistle. However, that’s not the case in the United States.

Since it was introduced to America in the early part of the 20th Century, the yellow star thistle has spread faster than a California wildfire and now covers some 15 million acres, just in this state alone. It is also considered a noxious, invasive weed in 35 other states. But the honeybees don’t care as long as there are enough of those yellow blooms to get them through the dog days of summer.

Twelve Reasons to Grow Your Own Food

Doctors tell us we should eat fruits and vegetables for our health. Fresh is best. For more reasons to grow your own food, read on.

1. Enjoy Superior Flavor and Higher Nutritional Value

The flavor of produce that travels from your edible garden to your plate is far superior to that of store-bought varieties. Even before fresh produce reaches the bins of your local store, the fruits and vegetables must be picked, sorted, crated, and transported from suppliers t0 supermarkets and grocery stores. Time spent in transporting and storage can diminish food flavors and nutrient values.

2. Keep It Pesticide-Free

Go organic. Choose alternative methods (companion planting and organic sprays, for example) to treat garden pests and plant diseases. Organic farming starts with nourishing the soil, which in turn, nourishes the plants that nourishes a healthy body. Organically grown fruits and vegetables picked fresh, immediately prepared, and served are nutritionally superior than their commercially grown and stored counterparts.

3. Safeguard Your Health

Avoid the cancer-causing agents and toxic chemicals in pesticides that are commonly used on many commercially grown food products.

4. Cultivate Plant Diversity; Preserve History

Grow varieties of the vegetables and fruits you love. Or, choose cultivars that might have grown in your grandmother’s garden–a nod to preserving history. Or, plant varieties that have fallen out of favor, are unusual, or are even rare.

5. Lower Your Food Bill

Grow your own edibles and preserve them for later consumption (like freezing spring peas for a fall or winter meal). Preserving the bounty by drying or freezing or canning can reduce your grocery bills. Another cost and time saver is to grow hard-to-find varieties of heirloom herbs, vegetables, or fruits instead of tracking down sources for those items.

6. Expand Your Knowledge of Plants

Understanding the seed-to-harvest cycle in nature fosters deep appreciation for ecology and the environment and contributes to your knowledge about various plants’ needs for nutrients, water, light, and temperature. You also learn about treatment options for garden-variety pests and plant diseases. This wealth of information can be shared with younger generations who will inherit the responsibility of caring for the planet.

7. Get Exercise

You can still work out, albeit in the garden in the fresh air rather than in an indoors gym. Think about all the exercise you’ll get digging, planting, shoveling, watering, weeding, and composting. Gardening provides plenty of solid exercise and rejuvenates a weary spirit.

8. Reduce Your Stress

Time spent in a garden is restorative: it nourishes your spirit and reduces stress levels. In fact, just a few moments of deep breathing and thinking about birdsong, sunshine, fresh air, and healthy plants all around you–nature in all its splendor–can generate a positive mental attitude.

9. Alleviate Concerns about Food Safety and Quality

You know the quality of the food you bring from your edible garden to the table. You want the superior freshness, flavor, and food quality for your loved ones. The chances for food-borne illnesses of the kind that strike Americans every year and are often investigated by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) are vastly diminished when you grow organic edibles and eat them as fresh as possible.

10. Preserve Our Planet’s Diversity

Choose seeds that are open-pollinated, non-GMO (genetically modified organism; the result of scientists engineering or modifying the genetic material of food plants). It may come as no surprise that the health of our nation has declined with the demise of small family farms even as there’s been a rise in the number of supermarkets and expansion of modern agribusiness. It’s no wonder people everywhere are getting behind buy-local, keep-it-local movements; participating in farmers’ markets, and engaging in urban homesteading where self-reliance is paramount.

11. Earn Extra Money

Selling your home-grown produce to others in your community means you can make possible the goodness of organic produce to others while earning a little money (hint: buy more seeds or otherwise reinvest in your garden).

12. Feel Good about Donating Excess Produce to a Food Bank

Your local food bank or (sometimes churches, too) will distribute donated produce to needy families. Let it be a source of joy for you that your gardening efforts have literally put food in the mouths of those in less fortune life circumstances.

Early December Farmette Chores

I arose early today as I have for the last few months, eager to greet the rising sun even as the days grow shorter as we head toward the winter solstice. I stand with eyes closed facing east until the light blazes against my lids, almost lighting my being from the inside. Then I say prayers–my way to start the day off right.

The fruit trees have changed leaf color and dropped most of their foliage. I helped them along today, collecting up all the fallen leaves and putting them in the green recycle bin. With the leaves gone, I can use an organic spray to prevent overwintering of fungi and pests. Similarly, I pluck the leaves from the tea roses and cut the canes to a height of between 12-18 inches.

With the spade, I turned the soil around the base of most of the fruit trees to aerate the soil in preparation for adding some amendments like compost. I twisted the remaining pumpkins off the vine and tossed the vines (which were still blooming and setting up fruit) into the compost pile. It’ll be freezing soon, so I’m just getting a head start.

I put food in all the bird feeders and hung some suet for the woodpeckers. Finally, I raked an area under the pepper tree for the new, smaller hen house that Carlos will build sometime this month since we plan to acquire some new chickens in January. In all, it has been a very productive day . . . one of many scheduled for this month, the last month of the year.

Facebook

Facebook Goodreads

Goodreads LinkedIn

LinkedIn Meera Lester

Meera Lester Twitter

Twitter