Archive for December, 2012

Cape Honeysuckle Provides Blazing Color in Winter Gardens

Throughout the fall and winter in Northern California gardens, when summer blooms have disappeared and spring is still several months away, the flower clusters of Cape honeysuckle add brilliant orange-red color to drab landscapes. This climbing evergreen vine can reach 15 to 25 feet and looks stunning spilling over a fence. It can also be trained to cover a trellis or an arch. With vigorous pruning, the plant can be kept to a shrub of six to eight feet.

The name Cape honeysuckle refers to South Africa’s Cape Horn where the plant is indigenous. The name, therefore, misleads for the plant does not belong the true honeysuckle family (Lonicera).

Gardeners value the plant for its landscaping qualities that include brilliantly colored tubular flowers against fine, glistening green foliage. The plant is a rapid grower and can tolerate some drought although it needs good drainage. Vines that lie on the ground can root. The plant can also be grown from seed or cuttings.

I’ve found Cape honeysuckle to tolerate the sometimes harsh conditions of summer here on the farmette that might include days of triple digit outdoor temperatures and occasional high winds. The plant needs water in extreme heat, but once established seems vigorous and hardy.

Keep your pruning shears handy. I previously grew Cape honeysuckle in my San Jose garden where it was planted in an area of light shade. It rapidly climbed into the highest branches of an adjacent apricot tree.

Cape honeysuckle’s brilliant orange-red tubular flower clusters provide drama in an otherwise lackluster winter garden . Try the plant espaliered against a wall or allow it to scramble along a berm or bank.

For more information, see http://tinyurl.com/adv9q4w or http://tinyurl.com/bxxd22y.

Taking Geranium Cuttings

- Common geranium (Pelargonium hortorum)

The rainy season in Northern California is the perfect time of year to take geranium (Pelargonium) cuttings to plant in new pots, window boxes, or start in moisture-laden earth. Most geraniums aren’t too particular about soil quality. Cuttings are fairly easy to start by sticking them right into the ground and watering well.

Geranium is the common name for plants that botanists call by the species name of Pelargonium of which there are several varieties. The rose geranium (Pelargonium graveolens) has richly fragrant leaves that remind me of an old country garden. The leaves are often used in potpourri, sachet, and even jelly or custard. I love brushing against the leaves of this plant in the garden as doing so releases its fragrance into the air.

Garden geraniums (Pelargonium hortorum) are hardy little plants that adapt quickly to the location where they are planted. We took a few cuttings with permission from our neighbor’s yard last year of a white geranium and now have a long row of them.

Also last year, my daughter gave me cuttings of her pink geranium. I plunged those cuttings directly into wet earth about this time last year. The cuttings have grown into a large bushy plant that produces lots of pink blossoms from spring to fall.

Last spring after rescuing a honeybee swarm two miles away in an orange tree of a neighbor’s yard, we received a cutting of his prolific Martha Washington geranium (Pelargonium domesticum). These geraniums are shrubby, upright and spread to roughly three feet. The dark green leaves provide a lovely foil for the large and showy flowers. This type of geranium needs daily watering during the warm weather.

Geraniums are easy to grow, some have lovely scents (lemon, nutmeg, and rose, for example), and many have pretty leaves that provide interest against a garden shed or stone wall.

All geraniums can be grown in pots and bloom best when they become pot-bound. Pinch growing tips back after blooming to get lots of new blooms. Feed twice during growing season. Then forget about them. Depending on the mother plant, cuttings will produce geraniums with bloom colors ranging from white and pink to red, lavender, and purple.

Nuts and Honey Add Lovely Flavor to Dried Fruit Tart

Flaky tarts piled high with fresh organic berries has always been for me a delightful way to end a summer meal. With the onset of winter now only eleven days away, I flip through my recipe files for something similar to those lovely summer tarts and hit upon an easy-to-make tart filled with dried fruits, nuts, and honey.

You can substitute or add other dried fruit (cranberries, figs, dates, and raisins, for example) to this tart, but I’ve found the best flavor comes from the dried peaches and apricots. They combine beautifully to create a richly flavorful dessert. A dollop of whipping cream on top adds a layer of decadence to this rich autumn tart.

Pastry Ingredients:

1 1/4 cup flour

1/4 cup sugar

1/2 cup unsalted butter (cut into pats or small pieces)

pinch of salt

1 large egg yolk

Directions for Pastry:

Combine pastry ingredients in a food processor with metal blade. Process until the mixture becomes a fine crumble. Add egg yolk and process into dough. Pastry should hold together, forming a ball.

Filling Ingredients:

3/4 cup white dessert wine

3/4 cup honey

18-20 dried apricots and/or peaches

1/2 teaspoon grated orange rind

1 cup blanched whole almonds

3 eggs

1 teaspoon good quality vanilla

2 Tablespoons unsalted butter

1 cup walnuts

Topping:

1 cup cream

1/4 teaspoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon of sugar

Directions for Toasted Almonds:

Preheat oven to 350 degrees Farenheit.

Toast blanched almonds on a baking sheet for 10 minutes. Remove and set aside. Keep oven on for baking the tart.

Directions for Tart Filling:

In a stainless steel pan, add the dried fruit with the orange rind.

Pour over the fruit and rind half the wine and 2 Tablespoons of honey.

Cook over low heat for 20 to 25 minutes until the fruit absorbs the liquid and plumps up, becoming soft and plaint.

In a bowl, combine eggs, honey, remaining wine, vanilla, and butter.

Beat in the walnuts and almonds.

In a springform pan, press the dough as thinly as possible over the bottom and up the sides of the pan. Drop the fruit onto the dough, spreading around over the bottom of the pastry. Pour in the nuts and egg mixture. Use a spatula to smooth the filling.

Bake the tart for 45 minutes on the middle rack of the oven.

Allow the tart to cool in its pan before removing and placing on a serving plate.

Whip cream until peaks form and fold in cinnamon and sugar. Put a dollop on top of each individual serving.

Serves 8.

Beekeepers: Take Note of Your Local Regulations

Backyard beekeeping has become a hot hobby . . . and it has come at an important juncture in the history of our planet. For several years, honeybee populations have been dwindling and bees mysteriously disappearing in Europe and America. This is worrisome since the bees are necessary for pollination of crops.

Perhaps you live in a city or town that supports beekeeping and has written that support into the municipal code or state law. Count yourself lucky to have all those little honeybees to pollinate your garden–even if you aren’t the beekeeper. But if you love honey, like I love honey you’ll want your own hive.

Before you go shopping for your beekeeper suit, check out your town’s municipal code and zoning regulations that cover the keeping of bees. Also, find out what state regulations might apply. Your town might not even permit beekeeping.

California law requires beekeepers to notify their counties. Having the law on the books, however, doesn’t necessarily mean the law is rigorously enforced. Lack of funding for oversight and enforcement makes it difficult to ensure the community’s beekeepers are compliant.

You might have to spend a little time trying to decipher the language in your municipality’s documents. Cities in the San Francisco Bay Area, have ordinances and regulations governing beekeeping that differ as widely as the language (contained in their documents) used to characterize bees. Bees as livestock . . . or exotic animals. Really?

Foster City and Fremont, both south of San Francisco, but on opposite sides of the bay, ban beekeeping. Further south, the cities of Palo Alto and San Jose require permits. So do some cities north of San Francisco, including San Rafael, Sausalito, Fairfax, and Tiburon. In Concord, it is unlawful to keep hives or maintain an apiary in the city, except under certain conditions. No hive within 25 feet of the property line and a sign at the front of the property advising of the presence of bees.

If you are a honey loving, aspiring beekeeper/gardener, I hope you are in one of those towns across America that recognizes the value of these little pollenizers. The populations of these beleaguered, little creatures are dwindling as if they were under siege. When your city/county/state supports your efforts (with the honeybees, of course), everyone wins. Best of all the honeybees and the planet wins. Imagine having to pollinate the gardens and fields of the world by hand. Now that’s a sobering thought.

Pruning Sixty-Year-Old Citrus Trees

When a friend who owns a house in San Jose asked for help in pruning her citrus trees (a lime, satsuma mandarin, and a grapefruit) during the first weekend in December, we agreed. The house had a lovely stone courtyard with two large citrus trees that had remained prolific producers in spite of being neglected for the last 20 years. The trees had been planted, she told us, approximately 60 years ago by an aunt.

Standard size citrus trees can reach 20 to 30 feet and spread almost as wide. Dwarf citrus, however, only reaches four to ten feet. The latter can be grown as landscape specimens or in pots where they can be easily moved around to protect them from frost and wind. In really hot, dry conditions, citrus in pots may need daily watering.

Once in San Jose, we checked the trees for diseases and pests. Aside from some of the lime leaves that had turned yellow, suggestive of too either much water or iron chlorosis (simply corrected with a little iron sulfate or chelated iron), the trees otherwise looked pest-free and loaded with ripe fruit.

Wearing gloves and long sleeves to protect against thorns, we shook the trees vigorously to remove unpicked fruit of previous seasons and the current season’s ripe fruit. The shaking yielded a five-gallon bucket and two partially full contractor bags of delectable limes and satsuma mandarins. The owner was delighted to have so much fruit. She even offered us some to make into marmalade, but we explained we had plenty of our own citrus on the farmette.

We carefully pruned out all the old dead branches and began shaping the trees, lifting and cutting branches that pointed down, removing crossed-over limbs, and cutting away branches that compromised the courtyard fence. Our work reduced the height and width of the trees (making it easier to harvest any fruit still hanging).

The work went smoothly. We even had time to tackle the ragged-looking grapefruit tree in the back. By the end of the day, we had freed three beautiful trees from a tangle of dead limbs and picked many pounds of fruit. The trees were once again serving the purpose for which they were planted–heavy producers that enhanced the beauty of the landscape.

Gravel Paths Lend Elegance to a Garden

Carlos, my husband, and I conceived our garden plan after we moved onto the farmette and realized the limitations of the land. The soil in this east bay valley in many places is compacted clay. Many areas around our farmette needed turning and aerating as well as nutrient amendments. If we wanted to plant fruit trees, berry vines, and flowers of all kinds, especially those attractive to honeybees, we needed good soil everywhere except under the gravel paths.

Putting in gravel paths made economical sense after we decided to build some large boxes for raised beds. Between the boxes, we planted trees. We envisioned the paths running either behind the boxes or in front of them. Our master plan continues to evolve, even as we work on the land–developing it and renovating the farmhouse.

The first step was to prepare the path area. We pulled out weeds, removed rocks, and turned the earth with a rototiller. Then we raked and compacted the soil.

We laid out the rows for the paths and installed pressure-treated wood held in place with spikes to keep the paths where we wanted them. In some cases, we had to build retaining walls. Then, we put down black plastic weed barrier paper, and hauled in the gravel.

Gravel comes in sizes ranging from rice grains all the way up to basketballs. Anything bigger than two feet is considered a boulder. We chose the pea-to-nickel size. We also created gravel walkways alongside the house and we used the same gravel in our large circular driveway.

A gravel path can lend an elegance to a landscaped space. On a trip to the United Kingdom, I visited country houses, castles, and gardens where I found gravel generously used on paths and in driveways. Here on the farmette, I really appreciate not getting my boots and shoes muddy during our Northern California rainy season. Our gravel paths make that possible.

Saving and Sharing Seeds

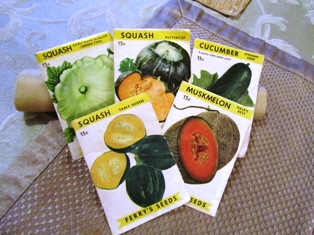

Packets of Ferry’s Seeds imprinted on the reverse with the words, “Packed for season,” and stamped 1958

Saving and sharing seed dates back to thousands of years before our forefathers brought their favorite heirloom seeds from their countries of origin to plant in their American gardens and fields. My grandmother, a frugal Scots-Irish farm woman, taught me by example how to save seed. I was six when I went to live with her in Boone County, Missouri. Our daily chores began before dawn.

She would strain the warm milk my grandfather brought from the barn after he had milked the cows. I was dispatched to the chicken house to collect eggs, sometimes from underneath hens still sitting on them. She would begin cooking the first of three hearty meals for the day.

With the breakfast dishes done, my grandmother and I would tend the vegetable gardens. We would hoe and weed by hand until the sun got high or until Grandma had decided which vegetables she wanted to include in the noonday meal. If her choice included tomatoes or beans, for example, they were gathered in baskets along with produce from her favorite plants from which she would remove and preserve the seeds.

She dried and stored the seed in paper envelopes or bags or glass jars. These she kept for planting in future gardens. The saving and sharing of seed among farmers and gardeners of my grandmother’s era and her ancestors was a traditional practice. Today, the practice continues with organic and home gardeners who share the belief that seed biodiversity must be ensured in keeping with natural evolutionary processes.

Today, commercial seed companies and corporations commonly file patents on seeds they have hybridized or cloned, making it illegal for farmers and gardeners to sell or otherwise distribute the seed. The hybridization produces a particular plant (that may have resistance to certain diseases or pests or display an unusual color, for example) in its first year, but second-generations of such hybrids may not come true. More alarming is the suggestion that reliance on commercial hybridized seed means the loss of thousands of varieties of open-pollinated plants such as those my grandmother grew.

Open-pollinated plants remain true to type and yield when planted from seed collected from the parent plant during the previous year. Some backyard gardeners, farmers, and plant growers today eschew using seed that has been genetically modified. They favor organic heirloom seed and are fueling an enthusiastic grass-roots effort to preserve the practice of saving and sharing seeds.

Pomegranate: A Jewel of a Fruit with a Long History

This time of year, you’ll find plenty of pomegranates in the markets and on harvest festival tables. It’s an important fruit in Middle Eastern cuisine. In the fall, pomegranate plants produce garnet-colored fruit with a leathery rind.

The fruit ranges in size from that of a large apple to a small kumquat (for ornamental types of pomegranates). The pomegranate’s treasure, however, is hidden inside. There you’ll find bright red juice and glistening seeds that taste sweet or bittersweet and astringent.

The pomegranate was known to the ancient world. Long before the birth of Christianity, the Egyptians viewed the fruit as a symbol of prosperity. The Bible contains numerous references to the pomegranate and its symbolism as an image of fertility.

The fruit is indigenous to Persia (the area that includes the modern countries of Iran and Iraq). The pomegranate’s popularity has spread since ancient times throughout the Middle East, India, Asia, and elsewhere around the world.

Pomegranate has important uses in the ancient Indian Ayurevedic system of medicine, including as a counterbalance of diets high in sugar and fat. In Northern California’s east bay valleys, the plant is easily cultivated. Our neighbors to the left, right, and rear of our farmette all grow pomegranates.

There are many cultivars of the plant (bushes, trees, and ornamental varieties). Our trees are young and still pretty small. The branches are stiff and tend to arch. Small oval leaves create a delicate open pattern–almost a lacy look–in the garden.

The best method of propagation is through cuttings from wood that is at least a year old. The plants are excellent landscape choices. They are not too picky about soil and as they get older are somewhat drought tolerant. Grow in full sun and irrigate young plants. You[ll be rewarded with trees that remain relatively pest-free and bear plentiful fruit.

Ripe fruit still hanging on the tree can split open, revealing the seeds. But many who grow this fruit and appreciate its nutrient, antioxidant, and medicinal value seldom leave these gems on the tree to over-ripen and fall.

Slow Moving Storms Saturate the Farmette

The meteorologists on Bay Area television warned for a week that a series of slow-moving storms would hit the region in a one, two, three punch. One weather forecaster explained that the cloud cover of the storms stretched from San Francisco to Hawaii. On our Henny Penny Farmette, the storms dropped a lot of water but the septic handled the deluge well.

Over the summer months, we had relocated mounds of earth to strategic areas so the water of these types of winter storms would flow away from the house. A walk around the farmette today convinced me that we did the right thing. Mostly, the water stayed away from the house foundation. Also, the French drain that encircles the perimeter of the house seems to be working well.

Still, the storms that dropped nearly eight inches of rain in the north bay, triggering emergency flash flood warnings for local streams and rivers, also saturated our farmette. Water pooled on some of our gravel paths. The largest reservoir of standing water is in front of the house. That area has been excavated for construction of our wrap-around porch and steps.

After enduring a hot, dry summer, the plants that are wintering over seem to come alive in the rain. In particular, the irises in beds around the farmette are starting to bloom. The French perfume lavender is also sending forth purple flower spikes. Whether it is summer heat cracking the ground or winter rains that saturate and flood it, each season has challenges but also offers gifts. To live in harmony with Mother Nature is be accepting and ever-mindful of the way nature achieves balance.

Facebook

Facebook Goodreads

Goodreads LinkedIn

LinkedIn Meera Lester

Meera Lester Twitter

Twitter