Archive for the 'Gardening' Category

De-Seeding a Pomegranate

Pomegranates are known since biblical times as a food of the gods. When ripe, the fruit’s leathery skin often splits open, exposing the red seeds inside. The fruit hangs like a jewel from a strong stem that must be cut or twisted to release the fruit.

Ripe pomegranates have a leathery outer skin, membranes thicker than oranges, but sweet, juicy seeds inside

Inside a ripe pomegranate are hundreds of juicy, sweet seeds that resemble small pegs of sweet corn. Holding the seeds in place are membranes.

The ruby red juice will stain fabrics and your fingers, so you’ll want to be careful handling the fruit as you release the seeds. The juice will stain your cutting board, too, but that stain can be removed with a lemon juice or vinegar scrub.

Cut off the stem and the blossom end.

Make a long shallow cut from the top to the bottom and up the other side, but avoid cutting deeply to avoid damaging the seeds. Then rotate the fruit and make a second cut completely around. Make 6 or 8 such shallow cuts to create equal sections.

Pry open the fruit to expose the seeds (known as arils). Place the fruit into a basin of water for 5 minutes. Working over the basin, peel the skin off and strip away the membrane pieces to release all the seeds.

Pluck out the membranes and rinse the seeds in a strainer. They are ready to be tossed into salads, eaten fresh, or stored in an airtight container (not metal) for 3-4 days. The seeds may also be made into juice; however, straining the juice from the seed pulp will be necessary.

If you keep chickens, it might interest you to know they love fresh pomegranate seeds. Seeing a ripened fruit with its peel split open and seeds exposed is a temptation for them to peck at low-hanging fruit on the tree.

Why Seed Saving Matters

Harvesting seed from my favorite flowers and vegetables has become of ritual for me. Basically, the plants do the work. I just pick the dried pods or seed heads, make sure they have an optimal period of time and the right environment to continue drying, and then store and/or share them.

An heirloom rose, a raised box of open-pollinated vegetables or heirloom herbs, or a bed of flowers are easily integrated into this landscape to create a peaceful garden

With access to so many seed sources online and in local nurseries, some might wonder why I would bother collecting and saving seeds from plants I grow. The reasons are simple:

* Many open-pollinated heirloom varieties that I grow once were also grown in gardens generations before my time.

* It’s gratifying to know that through the plants we grow (without pesticides or altered through genetic manipulation), we can have pure and safe food that we grow ourselves.

* Crop diversity can only continue if gardeners and growers are saving seeds of diverse crop varieties.

* Harvesting seeds from what we grow completes the cycle of nature that takes place each year in our gardens.

According to Heirloom Gardener magazine, “Roughly 90 percent of the varieties that existed at the beginning of the 20th Century are extinct.” (Winter 2013-2014) That’s certainly a concern. We can’t bring back those varieties, but we can work together to try to stop further extinctions.

Passing on a garden is a great gift to the next generation. Passing on seeds is equally laudable. Saving seeds matters . . . for all of us who believe in preserving plant diversity.

Growing and Sharing Farmette Figs

It’s that time of year when our fig trees reward us with a second crop of sweet, juicy fruit, best eaten right from the tree.

We aren’t the only ones who love to eat figs. The birds and raccoons are leaving telltale marks that they’re helping us devour this sweet fruit. And it’s no wonder.

Figs are a nutrient-rich food with antioxidant properties. They contain magnesium, vitamin B6, fiber, and beneficial amounts of calcium and iron.

We grow a couple of varieties of figs on the farmette–a White Genoa and Brown Turkey. Our neighbors also have towering fig tree with a canopy that reaches over the neighbor’s house. The tree is loaded now with baseball-size, dark purple fruit. I believe it’s a Black Mission fig, introduced into California by Father Junipero Serra who planted them in 1769 at the San Diego mission.

Our Brown Turkey fig produces a crop twice each year. The first crop, known as the breba grows on last season’s wood. The second, and more abundant crop, grows on new wood.The fig has rose-colored flesh inside a brownish-purple skin that tends to crack open with the fig is overripe.

The White Genoa is self-fruitful and has yellow-green skin with strawberry-colored pulp. The taste is mild and sweet and can be enjoyed as fresh fruit or paired with tangy goat cheese. The tree bears two crops each year and benefits from a vigorous pruning in the autumn after the figs are harvested.

Both figs will lose their leaves, leaving only their bark color and scaffolding as winter interest in the garden. The White Genoa’s bark is light gray whereas the Brown Turkey has a darker shade of grayish-brown bark.

These trees can be grown in containers and kept to about six feet tall for people who don’t have a lot of space for a tree that can otherwise reach 15 to 20 feet.

Figs aren’t fussy about soil, but won’t tolerate excessive water. They like the sun and are pretty hardy here in Northern California. Many figs are self-fruitful, but keeping bees means I have pollinators to help the fig crops along.

Collecting and Storing Sunflower Seeds for Next Year’s Garden

Drying heads of sunflowers and storing the seeds is easy. If your sunflowers have dry heads, ranging in size from saucers to large dinner plates, and they have turned brown and most of the petals have fallen off, the seeds are ready for harvesting.

Simply place a paper bag over the drying head and band it or tie with string to keep the birds and squirrels from foraging. Trust me, they’ll eat all your seeds if you permit it. The bag keeps the seed from dropping onto the ground to be foraged by wildlife or to generate new plants.

I like to the cut off the head, leaving eight or so inches of stem on it. This way, there is stem to tie and hang so that the head is positioned upside down in a bag. This position can facilitate the drying and captures all the seed while hanging in a drying shed. Retain this bag of seeds for replanting. The seeds are how the sunflower reproduces itself. Sunflower heads can hold thousands of seeds, depending on the size.

A word of caution here: don’t harvest the seeds and leave them drying in a tray in your shed the way I did. That will attract rodents. A coffee can with a plastic lid works great for storing sunflower seeds.

The best seeds for snacking are the gray and white striped sunflowers. There are other types of seed–for example, a black one and grayish-white seed, but the striped seeds are delicious. After you chew open the hull and spit it out, there’s a lovely seed inside it that tastes great and is nutritious.

Bougainvillea Vines Are Valued for Their Vibrant Color

If you’re looking for something that gives dense cover with green leaves and has prolific flower production, think about planting some bougainvillea vines. After my husband recently picked up four bougainvilleas in gallon-pots from our local nursery where the plants were on sale, we planted them around the front porch.

When you buy them in pots during spring and summer, you can pick bract color. The nearly inconspicuous blooms are surrounded by large, vibrantly colored bracts. Color choice ranges from red, orange, pink, fuchsia, deep purple, and white.

You’ll need to protect these evergreen shrubby vines where frost is expected. They’ll benefit from being moved to a warm wall. In fact, bougainvillea will thrive in the warmest parts of the garden. That said, they may even need a little shade protection in extremely hot areas.

Since the roots aren’t interwoven tightly in a root ball, you’ll want to plant them with care or slice the sides of your plastic gallon pot a half-dozen times, fold back, and plant pot and all in the planting hole.

Spring and summer are the best times to fertilize. Prune to renew the plant in the spring after the danger of frost is over. Many bougainvillea plants are tall growing varieties but you can also find some considered low- to medium-growing shrubs. These vines are show-stoppers with curb appeal and an even better value when you get them discounted at your local plant nursery.

Plum and Prune Trees Reward with Foliage, Blooms, and Fruit

We are growing several plum and prune trees here on the farmette, but because some were given to us as shoots from other people’s trees we don’t know the exact identity of some of our trees. However, the fruit from them is delicious.

A plum we are growing along the back fence of our property produces tons of bloom and lots of small-to-medium fruit with deep red coloring. The tree is self-fertile. Fruit aside, the tree has lovely dark reddish-purple leaves, spring to summer. We like the foliage so much that when it sprouted (plums love to sprout new shoots), we culled a couple of sprouts for new trees. Now we have three of those plums on our property and believe the cultivar to be a European Damson.

Another plum given to us is a yellow variety. The first year we lived here, that plum tree gave us a large-size crock bowl full of sweet, yellow, good-quality fruit. We believe it is self-fertile (although we keep honeybees and our neighbor’s have plum trees that quite possibly pollinate ours).

We are aware of a couple of yellow plums. One is a Japanese cultivar–Shiro–that produces a golden yellow plum with yellow flesh. Another is a European variety–Yellow Egg–that is self-fertile and produces large, oval, yellow-fleshed fruit. I do not know if the tree we are growing belongs to either of these types.

Last spring, we planted a self-fertile French prune–Agen. The fruit is small, red to purplish black with a sweet taste. It’s a late producer but is the standard drying prune for California. It can also be canned.

Plum and prune trees aren’t too fussy about soil, but they do respond to a feeding now and then. Japanese plums can easily take one to three pounds of nitrogen annually, while European plums will do well with one to two pounds of nitrogen.

Pruning is required. Japanese plums benefit from severe pruning at all stages (prune to a vase shape). European plums should also be trained to the vase shape and benefit from an annual pruning when the trees are mature to thin out shoots.

Thinning fruits (one fruit for every four inches) as soon as they form will yield stronger trees and larger fruit. As for pest, use an organic dormant spray for pests that winter over. Otherwise, plum and prune trees are joy to grow in the garden for their foliage, blooms, shade, and fruit.

Growing a Meyer Lemon Tree

Meyer Lemon is California’s favorite backyard fruit tree. Here, in the Bay Area, I am growing it on my farmette along with Satsuma tangerines, blood oranges, naval oranges, and lime trees. We love marmalade made from our citrus as well as juice, pickles, and desserts.

Leaving the tag attached for the first year can guide a gardener to caring for the plant according to grower recommendations

In two beds at the front of my property along a fence line, I’ve planted several citrus trees, among them, an improved Meyer lemon.

First introduced from China to the United States in 1908, Meyer Lemon takes its name from an agricultural explorer with the USDA named Frank Nicholas Meyer. These beautiful thin-skinned lemons are more round, juicier, and less acidic than their counterparts Lisbon and Eureka. It takes four years to grow one tree from seed. Today, the improved Meyer is widely available in California.

In the 1940s, Meyer lemons were believed to be carriers of the Citrus tristeza and tatter leaf viruses. Although these viruses did not harm the Meyers, it harmed other varieties of lemons grown by commercial growers. Ergo, the California department of Food and Agriculture dictated that the Meyer lemons would have to be eradicated. See, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meyer_lemon

In the 1950s a virus-free selection was identified and then in 1975, an improved Meyer was cloned. It tested free of those viruses, resulting in this new, “improved” Meyer Lemon again being planted in California. If you love the bright flavor and the clean, fragrant scent as well as the versatility of this lemon that can be roasted, salted in brine, drizzled into cake, made into pie, and even candied, consider planting an improved Meyer Lemon tree. They are vigorous growers that produce a bountiful crop.

Six Steps to Growing a Meyer Lemon

1. Plant in a container (the method many Chinese gardeners love) or in the ground.

2. Dig in a south-facing spot that will receive plenty of sunlight (at least eight hours per day).

3. Water when needed, but don’t over-water; this citrus likes a good drenching and then a chance to dry-out.

4. Four times per year, apply organic citrus fertilizer and water it into the roots.

5. Give support to young trees against wind, and thin fruit on young trees until they are are well established.

6. Prune off branches after the late winter/spring harvest to keep them (or the fruit) from touching the ground.

Gathering Seed for Next Year’s Garden

The sounds of summer around our farmette have grown quieter. It’s mid-August and the neighborhood children have returned to school. I miss their laughter. I miss the delight on their faces at seeing the chickens and the honeybees. I miss keeping them company at their lemonade stand.

But I admit to the secret pleasure of solitude and quiet, though it isn’t really silence. It’s the peaceful clucking of chickens and the twitter of songbirds as I gather seed from plants that have bloomed and dried, such as the cosmos, nasturtiums, sunflowers, and wisteria.

The wisteria vine that exploded in growth of long, green tendrils during spring and early summer and graced us with bracts of purple perfusion now hold heavy pods. The pods contain seeds that can be dried and planted for new vines next year.

The sword-shaped leaves of the irises are dry–their blooms a memory from early spring. I’ve already cut their long leaves back into four-inch fans and will dig some of the rhizomes for replanting in other beds around the farmette.

The sunflowers that the bees love to forage on have gone to seed. Those seeds will become next year’s plants, but some we’ll save for the squirrels.

The red and yellow onions have developed seed pods on long shoots now. I’ll plant those in raised beds in the fall for a spring crop of onions.

Yes, the dog days of summer have come around again. But the growing season continues. End of summer gives rise to autumn when grapes, persimmons, pumpkins, figs, and pomegranates ripen. On the farmette, there is always another season and other crops to look forward to with anticipation. It’s the good life.

A Potpourri of Tips and Tricks to Benefit Your Garden

Today’s blog is filled with miscellaneous tips and tricks that benefit the garden and also the environment.

1. Grow a cover crop–also known as green manure crop, planting a cover crop such as grasses or legumes after you’ve harvested your summer bounty can stop weeds from claiming the bed and also prevent soil erosion.

2. Mulch your garden paths–use pine needles, leaves, or old black-and-white newspapers, which are now often printed with soy ink.

3. Save empty jugs of tea, juice, milk–rinse and cut out the bottoms to use the jugs as hot-cap environments for tender seedlings.

4. Recycle gently used gray water–pour it on fruit trees and ornamental plants; but do not pour it on acid loving plants (gray water is naturally alkaline) so do not use it on leafy vegetables and root crops that are to be consumed uncooked.

5. Thin vegetable seedlings and hanging fruit–abundance has a down side since crowded plants don’t thrive as well or bulb as big (like onions). When fruit on fruit trees is thinned, the remaining fruit tends to grow larger.

6. Recycle plastic tubs–whether they once held yogurt, margarine, or soup from the health food store, turn them upside down in the garden to keep melons off the ground (prevents them from rotting)

Backyard Gardeners and Farmers Have a Choice

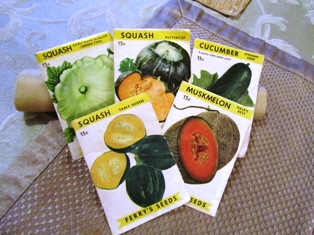

We gardeners and farmers have a choice when putting in our gardens, fields, and orchards. We can choose open-pollinated, heirloom seeds, hybrids seeds, or GMO seeds. I much prefer the old-fashioned way of seed-saving and sharing of open-pollinated, heirloom varieties.

On our farmette, we routinely save seed from plants we grow in one season and use them during another. We have picked apricots from our backyard trees, saved the seeds, and grown new trees that (this year) bore fruit.

We’ve exchanged seeds with our neighbors who also keep organic gardens and prefer open-pollinated seeds. Seeds that are hybrid and/or GMO usually are patented, meaning scientific companies or growers own those patents.

Open-pollinated seeds do not carry patents and remain available to all of us to plant and replant.

Gathering seeds from the plants one grows is how our grandparents did it. I go around plucking seed heads from cosmos, purple cone flower, and the hardened seeds of nasturtiums when the flowers have faded. I’ve taken cuttings of all my roses and have been given clips from friends and neighbor’s bushes and now plenty of roses to line walkways and fill a garden.

This year, an apricot tree that we started two years ago after we ate the fruit and planted its seed, bore beautiful cots that I turned into jam. I’ve got a bountiful crop of onions (red and yellow) and garlic and peppers this year from last year’s seed. The cycle goes on.

The acronym GMO stands for “genetically modified organism.” The phrase means that scientists have used recombinant DNA technology to create the seed. In some cases, the purpose is to create seeds with pesticides spliced into their DNA to repel pests.

Some gardeners see this process by chemists, scientists, and researchers working of large petro-chemical companies as a dangerous venture into biological processes that have a long evolutionary history. Further, the concern encompasses the potential negative ramifications of genetically engineering a plant–what farmer wants to handle seed (much less eat the plant) that has warning labels about pesticides integrated into the seeds?

If gardeners stick with open-pollinated seeds and participate in seed saving and sharing, together we can ensure our Earth’s biodiversity continues. The other prospect is scary. Many species and cultivars of plants are no longer available. They are no longer being grown. Some have become extinct.

Facebook

Facebook Goodreads

Goodreads LinkedIn

LinkedIn Meera Lester

Meera Lester Twitter

Twitter