Archive for the 'Gardening' Category

Plants for Sun Rooms, Solariums, and Conservatories

My husband and I grew exotic flowers in and around our Miami, Florida home. We had a sun room that sheltered a swimming pool in which I swam laps in every day. The space seemed near perfect for growing orchids in cycles of perpetual bloom. They loved loved the heat, light, and moisture provided by the pool and a fountain we installed. We also had an angel trumpet tree (Datura arborea) in the front of the house, adding drama and a luscious scent to the entry area.

But with the freezing winter temperatures on our Northern California farmette, such plants would not survive unless grown in a conservatory type of room with lots of warmth and light.

Since buying the farmette, my hubby and I have toyed with the idea of building such a space, also known as sun room, greenhouse room, tea room, and solarium.

A major consideration besides money and materials would be the direction the room would face. For our farmhouse, the direction (also known as “aspect”) could be north where the patio is already located or if positioned at the front of the house (where we had planned to create a wraparound front porch), the sun room or conservatory’s aspect would face south.

This Camellia japonica produces attractive blooms in early to mid spring and would do well in a cooler sun room

A north-facing aspect permits plenty of light but less heat. In a cooler conservatory or sun room, we’d use more foliage plants such as camellia, begonia, geranium, anthurium, Australian bottle brush, fuchsia, ficus, gardenia, campanula, hypoestes , and various types of ivy and palm. We could also grow Cymbidium orchids that like dappled shade during summer but bloom in the dead of winter.

A south or west direction ensures intense light and heat and would allow us to grow more flowering plants (especially ones found in the subtropics and tropics), including exotic orchids.

My husband grew up on a Caribbean island and loves orchids. The cymbidium orchids do well enough already outside. We put them in protected areas on frosty nights. But many of the exotic orchids require light, heat, and, in some cases, additional moisture.

We know Phalaenopsis, odontoglossum, and slipper orchids would thrive in a conservatory room that faces south or west as would many other plants such as hibiscus, jasmine, nephrolepsis, passion flower, plumeria, and African violet, to name a few. Also, many hybrid rhododendrons that profusely flower for long periods can be grown in containers in a warm environment.

I’m really an outside garden girl, but a conservatory room with a lot of interesting architectural detail and gorgeous blooming plants could make me want to spend more time indoors. It doesn’t matter to me whether it faces north or south. But dare I bring up the idea of adding a pool?

Gardens as Sacred Space

Painted with the French words for peace, love, and prayer, the blue trellis serves as a garden focal point

In seed time learn, in harvest teach, in winter enjoy.–William Blake

It feels like winter. No sun after a clear, cold night. The temperature at Lake Tahoe this morning was a level zero. Here on the farmette, the temperature is having trouble pushing out of the 40s. Though bleak outside, there is light and warmth in our little farmhouse. Soup gurgles in the pot on the back burner, and the seed catalogs are close at hand.

Remembering visionary poet William Blake’s admonishment to enjoy winter, I’m trying. The seed catalogs remind me of plants and gardens of my past, the great gardens of the world, and the secret places that all gardens hold–places awaiting discovery or re-discovery. Places that create magic in a garden.

My garden isn’t just a place to cultivate plants; it exists as sacred space, a tranquil retreat. There under trees and amid the roses that I invariably plant, my restless spirit knows its place and can find its peace.

Gardens are so much more than trees and flowers, chimes, statuary, benches, and fountains of flowing water. Far more important than what is visible in a garden is what is not seen . . . but felt.

A garden is a place of presence. One of my favorite writers John O’donohue, Anam Cara and Eternal Echoes) observed, “that presence is alive.” Sacred space beckons us to step away from the cacophony of the world and enter Kairos or God’s time to dream, create, pray, love, nuture Self, and experience the wild presences of Nature.

The best gardens always have a little surprise; this is a garden step I created some years ago while writing my Adventures in Mosaic book

We step in and out of the garden, a living and ever-changing landscape, but it is only when we linger in the landscape that we are embraced by the unseen–what O’Donohue referred to as silent and indirect presences.

A garden nourishes and nurtures. It was to the garden I turned after losing five family members in five years; my mother and my 46-year-old husband were the last to go. I hid myself away in our garden, turned on the water, and allowed my own tears to flow until none were left.

Later, I spent hours in the garden, mourning my loss, remembering my dreams, re-imaging my future, and praying for my aching heart to heal. Relief came as I created pique assiette mosaics and photographed them for a book to be published.

From broken china pieces and colored glass, I created a child’s tea table. When a local teacher told me about a girl in her class whose father needed a heart transplant and had no money for Christmas presents, I gave the table to his little girl.

In my garden, I found healing and wholeness and strength to again step into life. The power of sacred space can do that. It can uplift your spirit and nourish you with light and warmth when all seems so terribly bleak. Best of all, garden memories are bearers of light and joy, nourishing your spirit even on the darkest, coldest days of winter.

Herbs for Healing and Well-Being

For thousands of years, humankind has relied on the healing properties of herbs, plucked in the wild or cultivated in gardens, to treat what has ailed them. Modern holistic practitioners value herbs and plant-based medicines as integral elements in re-balancing the health of their patients and fostering wellness and robust vitality.

Doctors trained in allopathic or mainstream Western medicine traditionally have prescribed chemically based medicines (that usually have side effects). However, Western-trained doctors may also recommend the use of herbs for certain health issues. Always talk with your physician before starting any type of self-treatment with herbs. Keep your physician informed of herbs you may be taking. Herbs or herb formulations can interact or even block the efficacious effect of the medications your doctor has prescribed.

Dr. Andrew Weil, the Harvard-trained physician who pioneered the field of integrative medicine (combining mainstream and alternative medicine) and also wrote several best-selling books, suggests three specific herbs can reduce inflammation in the body–tumeric, ginger, and boswellia. These herbs can be found in specific doses formulated in capsules to make it easy to take the right amount. See, http://www.drweil.com/drw/u/QAA142972/Anti-Inflammatory-Herbs.com.

In traditional Chinese medicine, four herbs play vital roles in achieving a state of well-being. Rosemary stimulates brain alertness, mint aids in digestion, sage supports mental acuity, and parsley protects the eyes. See, http://www.doctoroz.com/blog/mao-shing-ni-lac-dom-phd/4-commonly-used-healing-herbs.

Whether herbs are used dried or fresh, made into a tea, tincture, culinary preparation, or packaged in capsules and other forms, they are often included as part of a larger health-focused program to restore and maintain a balanced, healthy body.

Ayurveda, a healing system used in India since ancient times, utilizes herbs in treatments that can encompass many healing modalities. According to Ayurveda, a balanced, healthy body depends on a strong metabolic and immune system, attained through proper nutrition, exercise, yoga, and meditation (to relieve tension and stress that can accumulate in the body and mind).

Herbs used in Ayurveda are many and include (but are not limited to) andrographis, ashwagandha, black mustard seed, cardamom, coriander, cumin, ginger, purslane (pigweed), tulsi (holy basil), tumeric, and visnaga.

During the medieval period, gardens of priests, convents, and cloisters contained the herbs that members of the clergy as well as ordinary people believed could treat or cure them of their ailments. In the twelfth century, German mystic Saint Hildegard of Bingen wrote about health and healing, detailing medicinal uses of over 200 healing plants.

Although most herbs are fairly easy to grow, take the time to learn about them. Provide for the plant’s needs (water, nutrients, sun or shade requirement). Find out when to harvest and how best to use the plant for your health and well-being. Find out what the negative factors might be in using a specific herb or medicinal plant. When you engage in this type of work, you continue a practice begun thousands of years ago that can have health benefits for you today. But don’t forget to have that discussion with your doctor before taking medicinal herbs.

Winter, Time of Dormancy for Figs and Other Fruit Trees

Only four days remain until the official onset of winter. Drifting leaves from the Mission fig tree towering above my neighbor’s rooftop catches my attention. The fig’s thick trunk and spreading branches form a scaffold that sways against the western sky, pushed by a storm wind advancing from off the Pacific. It took most of autumn for the grand old fig to shed its canopy. Now most of its leaves lie on the ground like pieces of a discarded garment in Mother Nature’s closet.

Human hands, raccoon paws, and squirrel feet removed the tree’s fruit over the summer and fall. The fig remains picturesque with its lowest branches as thick as its trunk and with some trunks gnarled and covered with green moss.

The grand old fig stands stark and vulnerable, soon to rest in complete dormancy, in contrast to its unabashed fecundity during summer. The tree must await spring’s light and warmth to reawaken. For now, the fig’s heavy, gray bark finds resonance in weathered buildings, barns, and fences built more than a half century ago in this part of Contra Costa County.

During spring and summer, when its sap is rejuvenated and flowing with life-giving nutrients, the fig sprouts a lush canopy of bright green leaves. Later, it prolifically produces sweet fruit that grow as large as a man’s fist.

Mother Nature isn’t as precise as the dates on our calendars.Her seasons ease seamlessly from one into another. Colder and darker days of winter are yet to come. For many plants, the season of cold and storms is a time of rest; a dormant period from which they will emerge anew. The fig will again blossom, leaf-out, produce fruit in a new cycle. This is the promise of spring, the hope of gardeners. Until then, the tree has earned a much-needed rest.

Winter Bounty of Fruit is “Preventative Medicine in Bowls”

The overnight temperature is expected to drop to freezing. The cold front moving through prompted my lovely neighbor Wajiha to offer me the gift of lemons and persimmons from her trees before the freeze hits. I had already been pulling off the ripe Satsuma mandarins and oranges from my own trees.

My husband and I will squeeze the juice from the lemons and freeze it with a little water, our version of frozen concentrate, to make lemonade. The need to remove the ripe fruit caught me by surprise or I would have had my marmalade recipe, preserve jars, and my canning equipment ready to make some marmalade or conserve.

Jam-making will have to wait as I’ve already made arrangements for cookie making and other holiday baking over this weekend. The Hachiya persimmons have turned a lovely orange color but are not yet soft. That means they’re still too astringent to eat.

As soon as the persimmons reach the jelly-soft state, I will be able to eat them or use them in pudding and baked goods. Persimmons are like an anti-aging fruit. They provide a rich source of powerful antioxidant compounds such as vitamins A and C, folic acid, beta-carotene, lycopene, and lutein. These compounds protect against free radicals that damage cells in the body.

The citrus fruits are a great source of vitamin C and help strengthen the immune system. So I’m looking at all this citrus in my kitchen and thinking how lucky I am to have all this “preventative medicine in bowls.”

Cape Honeysuckle Provides Blazing Color in Winter Gardens

Throughout the fall and winter in Northern California gardens, when summer blooms have disappeared and spring is still several months away, the flower clusters of Cape honeysuckle add brilliant orange-red color to drab landscapes. This climbing evergreen vine can reach 15 to 25 feet and looks stunning spilling over a fence. It can also be trained to cover a trellis or an arch. With vigorous pruning, the plant can be kept to a shrub of six to eight feet.

The name Cape honeysuckle refers to South Africa’s Cape Horn where the plant is indigenous. The name, therefore, misleads for the plant does not belong the true honeysuckle family (Lonicera).

Gardeners value the plant for its landscaping qualities that include brilliantly colored tubular flowers against fine, glistening green foliage. The plant is a rapid grower and can tolerate some drought although it needs good drainage. Vines that lie on the ground can root. The plant can also be grown from seed or cuttings.

I’ve found Cape honeysuckle to tolerate the sometimes harsh conditions of summer here on the farmette that might include days of triple digit outdoor temperatures and occasional high winds. The plant needs water in extreme heat, but once established seems vigorous and hardy.

Keep your pruning shears handy. I previously grew Cape honeysuckle in my San Jose garden where it was planted in an area of light shade. It rapidly climbed into the highest branches of an adjacent apricot tree.

Cape honeysuckle’s brilliant orange-red tubular flower clusters provide drama in an otherwise lackluster winter garden . Try the plant espaliered against a wall or allow it to scramble along a berm or bank.

For more information, see http://tinyurl.com/adv9q4w or http://tinyurl.com/bxxd22y.

Taking Geranium Cuttings

- Common geranium (Pelargonium hortorum)

The rainy season in Northern California is the perfect time of year to take geranium (Pelargonium) cuttings to plant in new pots, window boxes, or start in moisture-laden earth. Most geraniums aren’t too particular about soil quality. Cuttings are fairly easy to start by sticking them right into the ground and watering well.

Geranium is the common name for plants that botanists call by the species name of Pelargonium of which there are several varieties. The rose geranium (Pelargonium graveolens) has richly fragrant leaves that remind me of an old country garden. The leaves are often used in potpourri, sachet, and even jelly or custard. I love brushing against the leaves of this plant in the garden as doing so releases its fragrance into the air.

Garden geraniums (Pelargonium hortorum) are hardy little plants that adapt quickly to the location where they are planted. We took a few cuttings with permission from our neighbor’s yard last year of a white geranium and now have a long row of them.

Also last year, my daughter gave me cuttings of her pink geranium. I plunged those cuttings directly into wet earth about this time last year. The cuttings have grown into a large bushy plant that produces lots of pink blossoms from spring to fall.

Last spring after rescuing a honeybee swarm two miles away in an orange tree of a neighbor’s yard, we received a cutting of his prolific Martha Washington geranium (Pelargonium domesticum). These geraniums are shrubby, upright and spread to roughly three feet. The dark green leaves provide a lovely foil for the large and showy flowers. This type of geranium needs daily watering during the warm weather.

Geraniums are easy to grow, some have lovely scents (lemon, nutmeg, and rose, for example), and many have pretty leaves that provide interest against a garden shed or stone wall.

All geraniums can be grown in pots and bloom best when they become pot-bound. Pinch growing tips back after blooming to get lots of new blooms. Feed twice during growing season. Then forget about them. Depending on the mother plant, cuttings will produce geraniums with bloom colors ranging from white and pink to red, lavender, and purple.

Pruning Sixty-Year-Old Citrus Trees

When a friend who owns a house in San Jose asked for help in pruning her citrus trees (a lime, satsuma mandarin, and a grapefruit) during the first weekend in December, we agreed. The house had a lovely stone courtyard with two large citrus trees that had remained prolific producers in spite of being neglected for the last 20 years. The trees had been planted, she told us, approximately 60 years ago by an aunt.

Standard size citrus trees can reach 20 to 30 feet and spread almost as wide. Dwarf citrus, however, only reaches four to ten feet. The latter can be grown as landscape specimens or in pots where they can be easily moved around to protect them from frost and wind. In really hot, dry conditions, citrus in pots may need daily watering.

Once in San Jose, we checked the trees for diseases and pests. Aside from some of the lime leaves that had turned yellow, suggestive of too either much water or iron chlorosis (simply corrected with a little iron sulfate or chelated iron), the trees otherwise looked pest-free and loaded with ripe fruit.

Wearing gloves and long sleeves to protect against thorns, we shook the trees vigorously to remove unpicked fruit of previous seasons and the current season’s ripe fruit. The shaking yielded a five-gallon bucket and two partially full contractor bags of delectable limes and satsuma mandarins. The owner was delighted to have so much fruit. She even offered us some to make into marmalade, but we explained we had plenty of our own citrus on the farmette.

We carefully pruned out all the old dead branches and began shaping the trees, lifting and cutting branches that pointed down, removing crossed-over limbs, and cutting away branches that compromised the courtyard fence. Our work reduced the height and width of the trees (making it easier to harvest any fruit still hanging).

The work went smoothly. We even had time to tackle the ragged-looking grapefruit tree in the back. By the end of the day, we had freed three beautiful trees from a tangle of dead limbs and picked many pounds of fruit. The trees were once again serving the purpose for which they were planted–heavy producers that enhanced the beauty of the landscape.

Gravel Paths Lend Elegance to a Garden

Carlos, my husband, and I conceived our garden plan after we moved onto the farmette and realized the limitations of the land. The soil in this east bay valley in many places is compacted clay. Many areas around our farmette needed turning and aerating as well as nutrient amendments. If we wanted to plant fruit trees, berry vines, and flowers of all kinds, especially those attractive to honeybees, we needed good soil everywhere except under the gravel paths.

Putting in gravel paths made economical sense after we decided to build some large boxes for raised beds. Between the boxes, we planted trees. We envisioned the paths running either behind the boxes or in front of them. Our master plan continues to evolve, even as we work on the land–developing it and renovating the farmhouse.

The first step was to prepare the path area. We pulled out weeds, removed rocks, and turned the earth with a rototiller. Then we raked and compacted the soil.

We laid out the rows for the paths and installed pressure-treated wood held in place with spikes to keep the paths where we wanted them. In some cases, we had to build retaining walls. Then, we put down black plastic weed barrier paper, and hauled in the gravel.

Gravel comes in sizes ranging from rice grains all the way up to basketballs. Anything bigger than two feet is considered a boulder. We chose the pea-to-nickel size. We also created gravel walkways alongside the house and we used the same gravel in our large circular driveway.

A gravel path can lend an elegance to a landscaped space. On a trip to the United Kingdom, I visited country houses, castles, and gardens where I found gravel generously used on paths and in driveways. Here on the farmette, I really appreciate not getting my boots and shoes muddy during our Northern California rainy season. Our gravel paths make that possible.

Saving and Sharing Seeds

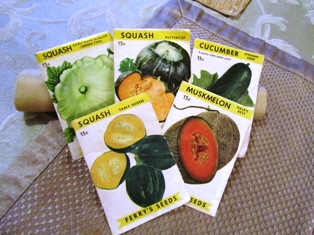

Packets of Ferry’s Seeds imprinted on the reverse with the words, “Packed for season,” and stamped 1958

Saving and sharing seed dates back to thousands of years before our forefathers brought their favorite heirloom seeds from their countries of origin to plant in their American gardens and fields. My grandmother, a frugal Scots-Irish farm woman, taught me by example how to save seed. I was six when I went to live with her in Boone County, Missouri. Our daily chores began before dawn.

She would strain the warm milk my grandfather brought from the barn after he had milked the cows. I was dispatched to the chicken house to collect eggs, sometimes from underneath hens still sitting on them. She would begin cooking the first of three hearty meals for the day.

With the breakfast dishes done, my grandmother and I would tend the vegetable gardens. We would hoe and weed by hand until the sun got high or until Grandma had decided which vegetables she wanted to include in the noonday meal. If her choice included tomatoes or beans, for example, they were gathered in baskets along with produce from her favorite plants from which she would remove and preserve the seeds.

She dried and stored the seed in paper envelopes or bags or glass jars. These she kept for planting in future gardens. The saving and sharing of seed among farmers and gardeners of my grandmother’s era and her ancestors was a traditional practice. Today, the practice continues with organic and home gardeners who share the belief that seed biodiversity must be ensured in keeping with natural evolutionary processes.

Today, commercial seed companies and corporations commonly file patents on seeds they have hybridized or cloned, making it illegal for farmers and gardeners to sell or otherwise distribute the seed. The hybridization produces a particular plant (that may have resistance to certain diseases or pests or display an unusual color, for example) in its first year, but second-generations of such hybrids may not come true. More alarming is the suggestion that reliance on commercial hybridized seed means the loss of thousands of varieties of open-pollinated plants such as those my grandmother grew.

Open-pollinated plants remain true to type and yield when planted from seed collected from the parent plant during the previous year. Some backyard gardeners, farmers, and plant growers today eschew using seed that has been genetically modified. They favor organic heirloom seed and are fueling an enthusiastic grass-roots effort to preserve the practice of saving and sharing seeds.

Facebook

Facebook Goodreads

Goodreads LinkedIn

LinkedIn Meera Lester

Meera Lester Twitter

Twitter