Archive for the 'Plants and Trees' Category

Collecting and Storing Sunflower Seeds for Next Year’s Garden

Drying heads of sunflowers and storing the seeds is easy. If your sunflowers have dry heads, ranging in size from saucers to large dinner plates, and they have turned brown and most of the petals have fallen off, the seeds are ready for harvesting.

Simply place a paper bag over the drying head and band it or tie with string to keep the birds and squirrels from foraging. Trust me, they’ll eat all your seeds if you permit it. The bag keeps the seed from dropping onto the ground to be foraged by wildlife or to generate new plants.

I like to the cut off the head, leaving eight or so inches of stem on it. This way, there is stem to tie and hang so that the head is positioned upside down in a bag. This position can facilitate the drying and captures all the seed while hanging in a drying shed. Retain this bag of seeds for replanting. The seeds are how the sunflower reproduces itself. Sunflower heads can hold thousands of seeds, depending on the size.

A word of caution here: don’t harvest the seeds and leave them drying in a tray in your shed the way I did. That will attract rodents. A coffee can with a plastic lid works great for storing sunflower seeds.

The best seeds for snacking are the gray and white striped sunflowers. There are other types of seed–for example, a black one and grayish-white seed, but the striped seeds are delicious. After you chew open the hull and spit it out, there’s a lovely seed inside it that tastes great and is nutritious.

Bougainvillea Vines Are Valued for Their Vibrant Color

If you’re looking for something that gives dense cover with green leaves and has prolific flower production, think about planting some bougainvillea vines. After my husband recently picked up four bougainvilleas in gallon-pots from our local nursery where the plants were on sale, we planted them around the front porch.

When you buy them in pots during spring and summer, you can pick bract color. The nearly inconspicuous blooms are surrounded by large, vibrantly colored bracts. Color choice ranges from red, orange, pink, fuchsia, deep purple, and white.

You’ll need to protect these evergreen shrubby vines where frost is expected. They’ll benefit from being moved to a warm wall. In fact, bougainvillea will thrive in the warmest parts of the garden. That said, they may even need a little shade protection in extremely hot areas.

Since the roots aren’t interwoven tightly in a root ball, you’ll want to plant them with care or slice the sides of your plastic gallon pot a half-dozen times, fold back, and plant pot and all in the planting hole.

Spring and summer are the best times to fertilize. Prune to renew the plant in the spring after the danger of frost is over. Many bougainvillea plants are tall growing varieties but you can also find some considered low- to medium-growing shrubs. These vines are show-stoppers with curb appeal and an even better value when you get them discounted at your local plant nursery.

Plum and Prune Trees Reward with Foliage, Blooms, and Fruit

We are growing several plum and prune trees here on the farmette, but because some were given to us as shoots from other people’s trees we don’t know the exact identity of some of our trees. However, the fruit from them is delicious.

A plum we are growing along the back fence of our property produces tons of bloom and lots of small-to-medium fruit with deep red coloring. The tree is self-fertile. Fruit aside, the tree has lovely dark reddish-purple leaves, spring to summer. We like the foliage so much that when it sprouted (plums love to sprout new shoots), we culled a couple of sprouts for new trees. Now we have three of those plums on our property and believe the cultivar to be a European Damson.

Another plum given to us is a yellow variety. The first year we lived here, that plum tree gave us a large-size crock bowl full of sweet, yellow, good-quality fruit. We believe it is self-fertile (although we keep honeybees and our neighbor’s have plum trees that quite possibly pollinate ours).

We are aware of a couple of yellow plums. One is a Japanese cultivar–Shiro–that produces a golden yellow plum with yellow flesh. Another is a European variety–Yellow Egg–that is self-fertile and produces large, oval, yellow-fleshed fruit. I do not know if the tree we are growing belongs to either of these types.

Last spring, we planted a self-fertile French prune–Agen. The fruit is small, red to purplish black with a sweet taste. It’s a late producer but is the standard drying prune for California. It can also be canned.

Plum and prune trees aren’t too fussy about soil, but they do respond to a feeding now and then. Japanese plums can easily take one to three pounds of nitrogen annually, while European plums will do well with one to two pounds of nitrogen.

Pruning is required. Japanese plums benefit from severe pruning at all stages (prune to a vase shape). European plums should also be trained to the vase shape and benefit from an annual pruning when the trees are mature to thin out shoots.

Thinning fruits (one fruit for every four inches) as soon as they form will yield stronger trees and larger fruit. As for pest, use an organic dormant spray for pests that winter over. Otherwise, plum and prune trees are joy to grow in the garden for their foliage, blooms, shade, and fruit.

Growing a Meyer Lemon Tree

Meyer Lemon is California’s favorite backyard fruit tree. Here, in the Bay Area, I am growing it on my farmette along with Satsuma tangerines, blood oranges, naval oranges, and lime trees. We love marmalade made from our citrus as well as juice, pickles, and desserts.

Leaving the tag attached for the first year can guide a gardener to caring for the plant according to grower recommendations

In two beds at the front of my property along a fence line, I’ve planted several citrus trees, among them, an improved Meyer lemon.

First introduced from China to the United States in 1908, Meyer Lemon takes its name from an agricultural explorer with the USDA named Frank Nicholas Meyer. These beautiful thin-skinned lemons are more round, juicier, and less acidic than their counterparts Lisbon and Eureka. It takes four years to grow one tree from seed. Today, the improved Meyer is widely available in California.

In the 1940s, Meyer lemons were believed to be carriers of the Citrus tristeza and tatter leaf viruses. Although these viruses did not harm the Meyers, it harmed other varieties of lemons grown by commercial growers. Ergo, the California department of Food and Agriculture dictated that the Meyer lemons would have to be eradicated. See, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meyer_lemon

In the 1950s a virus-free selection was identified and then in 1975, an improved Meyer was cloned. It tested free of those viruses, resulting in this new, “improved” Meyer Lemon again being planted in California. If you love the bright flavor and the clean, fragrant scent as well as the versatility of this lemon that can be roasted, salted in brine, drizzled into cake, made into pie, and even candied, consider planting an improved Meyer Lemon tree. They are vigorous growers that produce a bountiful crop.

Six Steps to Growing a Meyer Lemon

1. Plant in a container (the method many Chinese gardeners love) or in the ground.

2. Dig in a south-facing spot that will receive plenty of sunlight (at least eight hours per day).

3. Water when needed, but don’t over-water; this citrus likes a good drenching and then a chance to dry-out.

4. Four times per year, apply organic citrus fertilizer and water it into the roots.

5. Give support to young trees against wind, and thin fruit on young trees until they are are well established.

6. Prune off branches after the late winter/spring harvest to keep them (or the fruit) from touching the ground.

Backyard Gardeners and Farmers Have a Choice

We gardeners and farmers have a choice when putting in our gardens, fields, and orchards. We can choose open-pollinated, heirloom seeds, hybrids seeds, or GMO seeds. I much prefer the old-fashioned way of seed-saving and sharing of open-pollinated, heirloom varieties.

On our farmette, we routinely save seed from plants we grow in one season and use them during another. We have picked apricots from our backyard trees, saved the seeds, and grown new trees that (this year) bore fruit.

We’ve exchanged seeds with our neighbors who also keep organic gardens and prefer open-pollinated seeds. Seeds that are hybrid and/or GMO usually are patented, meaning scientific companies or growers own those patents.

Open-pollinated seeds do not carry patents and remain available to all of us to plant and replant.

Gathering seeds from the plants one grows is how our grandparents did it. I go around plucking seed heads from cosmos, purple cone flower, and the hardened seeds of nasturtiums when the flowers have faded. I’ve taken cuttings of all my roses and have been given clips from friends and neighbor’s bushes and now plenty of roses to line walkways and fill a garden.

This year, an apricot tree that we started two years ago after we ate the fruit and planted its seed, bore beautiful cots that I turned into jam. I’ve got a bountiful crop of onions (red and yellow) and garlic and peppers this year from last year’s seed. The cycle goes on.

The acronym GMO stands for “genetically modified organism.” The phrase means that scientists have used recombinant DNA technology to create the seed. In some cases, the purpose is to create seeds with pesticides spliced into their DNA to repel pests.

Some gardeners see this process by chemists, scientists, and researchers working of large petro-chemical companies as a dangerous venture into biological processes that have a long evolutionary history. Further, the concern encompasses the potential negative ramifications of genetically engineering a plant–what farmer wants to handle seed (much less eat the plant) that has warning labels about pesticides integrated into the seeds?

If gardeners stick with open-pollinated seeds and participate in seed saving and sharing, together we can ensure our Earth’s biodiversity continues. The other prospect is scary. Many species and cultivars of plants are no longer available. They are no longer being grown. Some have become extinct.

Northern California Nut Trees in a Nutshell

Take a trip into Northern California’s great Central Valley and you’ll notice how the landscape becomes dotted with nut tree farms along with vegetable fields, fruit tree orchards, and dairy farms. While Texas dominates the pecan tree market, California’s big three nut crops are almonds, walnuts, and pistachios. With nut prices on the increase, backyard gardeners might consider planting a tree or two if they have the space.

Some nut trees, such as almonds, require pollination assistance–a couple of different cultivars and honeybees will do the trick. For this reason, commercial almond growers pay beekeepers to bring their hives in to pollinate California’s early almond crop each year. Growing almonds is big business in California (it’s the third leading agricultural product in the state); the decline in honeybee populations is bound to affect this profitable crop.

The Central Valley has the perfect climate and growing conditions for almonds. It’s estimated that there are roughly 5,500 almond growers in the state. Many are commercial growers who capitalize on the rich, well-drained soil, and the hot summers and cool winters of Northern California. But California’s continuing drought is causing concern to almond growers since almonds require a lot of water. Backyard gardeners, too, must consider the water requirement of almonds before planting trees.

A newly formed almond on the tree looks like an unripe fuzzy peach because almonds are related to the peaches. Mature almond trees reach 20 to 30 feet tall. Some popular cultivars in zones 5 through 8 are Hall’s Hardy, Nonpareil, Peerless, and Mission. My neighbors have gorgeous, healthy almonds growing on their farmette.

The California Black Walnut and Persian Walnut (with cultivars of Franquette, Chandler, and Hartley) are valued for their stateliness, shade, bountiful crops, and longevity. Walnuts contain healthy nutrients. Cultivars of the English walnut are fast-growing and the nuts are thin-skinned and bountiful.

If a walnut is planted at the birth of an individual, and he lives 75 years, that walnut tree might could still be growing when the person breathes his last breath. The black walnut can reach 100 feet in height. The nuts have an thick outer hull that can blacken sidewalks and driveways with their stain; also, the tree also can be toxic to other plants.

In comparison to walnuts, filberts/hazelnuts are considered small trees (achieving heights of only 10 to 40 feet), they are often the nut tree of choice for backyard landscapes. DuChilly and Daviana are excellent pollinizers with Barcelona. Other cultivars are Bixby, Royal, and Hall’s Giant.

Pecan trees grow much larger than filberts, often towering 70 to 150 feet. Some cultivars include Major, Peruque, Stuart, and Colby. The cultivars of Wichita, Western Schley, and Cherokee are excellent pollinators for each other. Of all the nuts valued for their antioxidants, pecans rank the highest.

There is a pistachio tree growing a mile or so from my farmette. While pistachios love the Mediterranean climate of the Central Valley, in some places the trees perform better than in others. The nuts are highly valued by consumers. Growers have taken notice. Pioneer Gold, a varietal that’s been around since 1976, remains a popular choice. The trees are wind pollinated and require a male and female tree for a crop set.

If you have room in a backyard garden or on a farmette or field, consider planting one or more nut trees. You’ll be rewarded with shade and heart-healthy, nutritional snacks for years to come.

Drying Fruits Naturally

I love dried apricots, but don’t tolerate well the ones treated with sulfur dioxide(used to prevent oxidation and loss of color). With so many apricots on our property coming ripe at once, I have decided in addition to making jam this year to also dry some of the fruit.

Apricots, so plentiful this time of year, are easy to dry and make great snacks when the season is over

Apricots dried but not treated with sulfur dioxide will turn a natural brown color. Some stores sell them this way. They are usually priced the same or similar to the treated apricots with the bright orange hue.

Besides apricots, other fruits that dry well include apples, bananas, cherries, grapes, nectarines, peaches, pears, plum, rhubarb, and even strawberries. You can use a drying machine

Quick Tips for Drying Fruit

1. Choose to dry only the freshest picked fruits, without bruises, scale, sun scald, or other blight.

2. Spray nonstick vegetable spray on drying pans or trays to make it easier to remove the dried fruit

3. Lay out the fruit to dry in a single layer on trays. Remember to rotate the trays occasionally and turn the pieces from time to time.

4. Destroy any insects (miniscule or otherwise) by freezing or baking the fruit. Simply take the tray and stick it into an oven heated to 175 degrees Fahrenheit for about 15 minutes. Alternatively, pack the dried fruit in freezer bags and freeze for at least 2 days.

5. Freezing dried fruit in resealable freezer bags will preserve its shelf life.

Fire Blight Can Ravage a Pear Tree or Take Down an Orchard

I’ve discovered limb tips, fruit, and blossoms blackened by fire blight in my Bartlett pear tree. That means dealing with the disease quickly or losing tree.

While there are dozens of other types of fruit trees on the farmette, there are no other pear trees. Sadly, this one is in bad shape because of a widespread infection by the bacteria Erwinia amylovora.

The blight started last summer and, despite spraying to control it, the disease has overwintered in the bark of the tree to reappear with the emergence of blossoms this year. Disease spread is helped along by the bees.

Fire blight’s vicious cycle and must be broken if the tree is to survive. The life cycle of blight can be seen at a glance at http://nysipm.cornell.edu/factsheets/treefruit/diseases/fb/fb_cycle.gif

Treatment starts with a vigorous pruning of the affected limbs. That means cutting back twelve inches from the site of the blackened area of fire blight. The disease is highly contagious, so the cuttings must not be recycled or composted. Burning them is recommended.

Also, minimizing the amount of tree blight inoculum in the orchard is important as this disease can also spread to other pear trees, apples, quince, raspberries, and fire-thorn bushes. Cornell recommends a regular spraying program using an appropriate bacteriocide to save fruit trees infected with fire blight.

The saddest thing of all for me is that the tree was once beautiful and healthy and (even now) is loaded with fruit. I hate to think of not being able to save this lovely pear tree. Since most pear cultivars are susceptible to fire blight, it might make sense for me to plant a Seckel Pear tree since it is less susceptible to this highly contagious disease that can destroy a single tree or ravage the entire orchard.

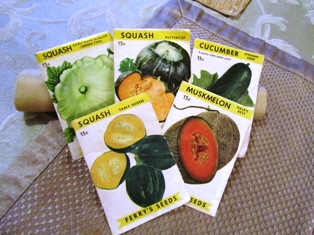

From Garden to Table, Easy-to-Grow Squash

I love summer squash, tossed into rosemary potatoes and served up with eggs and sausage on a Sunday morning; or, grilled with fish, or added to a freshly-made pasta sauce. Best of all, you can have it fresh, from your kitchen garden to your table, as squash is one of the easiest vegetables to grow. Squash is a super food, high in antioxidants, fiber, and Vitamin A.

Squash is one of the Three Sisters (corn and climbing beans being the other two), grown together as companion plants in the tradition of certain groups of Native Americans who planted these vegetables. A fourth sister might be the Cleome serrulata, the Rocky Mountain bee plant to attract pollinators for the beans and squash.

There is a scientific basis for growing these three together. The squash grows fairly large and spreads out, blocking weeds. The beans provide nitrogen to the soil. The corn shoots up a stalk that provides the support the beans need to climb. The three plants benefit each other.

Each year, I plant both summer squash and winter varieties such as butternut and pumpkin that have hard shells and store longer. All types of squash are easy to grow. They just need sun, water, and room. They aren’t fussy about soil.

Summer squash includes zucchini, yellow squash, and scalloped (or round) squash. Autumn/winter varieties require a longer growing period (up to 120 days) and include butternut, acorn, hubbard, and pumpkin.

Growing Tips:

Choose a well-drained, sunny spot in the garden for your squash.

Plant three seeds to a hill (roughly six inches apart).

When the squash are about a foot tall, thin to the healthiest seedling.

Water two to three times each week.

Harvest summer squash when still young; if left on the vine, the squash becomes tough.

Twenty Water Conservation Tips

California is in a historic drought. It’s our fourth year of below-normal rainfall and scientists, city governments, state lawmakers, and communities worry that this drought could run longer, perhaps even becoming a mega-drought. Wells are going dry, reservoirs in the state are lower than they’ve been in years, and water levels in rivers, lakes, and streams have shrunk.

Farmers have a right to be worried that their acreage may have to lay fallow. And what about the fruit and nut orchards? The Sierra snow pack that supplies much of the water to the Central Valley and Bay Area (where much of California and the nation’s food is grown) remains a fraction of what it has been in non-drought years. Salmon runs are being impacted. Water is getting more scarce and more expensive. And less food produced means higher food prices.

Recently, Governor Jerry Brown mandated water conservation throughout the state. Communities are implementing drastic measures to force their citizens to cut water use. But that doesn’t necessarily mean lower water bills if our communities have to buy water to make up a shortfall. Each of us must do our part.

Environmentalists value bamboo for its drought tolerance and landscape appeal; stone is an excellent element for zero landscaping and can be used with succulents or cacti

Twenty Tips to Cut Water Use

!. Install low-flow toilets and tub, sink faucets, and shower heads.

2. Use a front-loading washer rather than a top-loading version. The front-loading machines use roughly 20 gallons per load versus the 40 gallons of top-loading machines. We installed our energy-efficient front-loading washer when we moved in.

3. Wash laundry less often and make sure you set the machine for the right size load.

4. Take shorter showers with the drain closed. Capture the gently-used water in pails to recycle.

5. Use your energy-star dishwasher for cleaning dishes, glassware, and pans. You will use less water than by washing dishes by hand. But run the dishwasher only after it is full, not half-empty.

6. If you have a pool or hot tub, use a cover on it to prevent evaporation of water.

7. Wet your toothbrush, but then turn off the water as you brush your teeth.

8. Capture gray water (from the dishwasher, washing machine, shower, and sink). Gray water is gently used household water, not water from the toilet or sewer. Have a plumber install a gray water system to trees and plants on your property.

9. Completely turn off faucets to avoid drips. Also, fix any leaky faucets or water pipes.

10. Collect rainwater in plastic barrels and keep covered to eliminate the potential for mosquitoes breeding in the water.

11. Shower less often. Flush the toilet less often and never to flush away an insect or tissue. Use a lidded-waste can instead.

12. Use the broom to clean the sidewalk and driveway, not the garden hose and water.

13. Stop watering the lawn. Consider removing the lawn in favor of a landscape with drought-tolerant and indigenous plants. Or zeriscape, using bamboo, succulents, cacti, and stone.

14. Buy and use green products with the EPA-partnered WaterSense label.

15. Don’t throw out leftover ice cubes; use them to water a plant.

16. Never use running water to thaw meat or fish. Defrost overnight in the refrigerator.

17. Insulate water pipes to get hot water faster instead of running water through the faucet.

18. Install an instant water heater appliance under the sink to get hot water instantly rather than let the faucet run until the water gets hot.

19. When on vacation away from home, turn off the water softener to conserve water.

20. Recycle kitchen waste instead of putting it down the garbage disposal and running water. That recycled waste can become valuable compost for your garden and keeps it out of the septic system.

Facebook

Facebook Goodreads

Goodreads LinkedIn

LinkedIn Meera Lester

Meera Lester Twitter

Twitter